The Violence of Memory: Francis Bacon

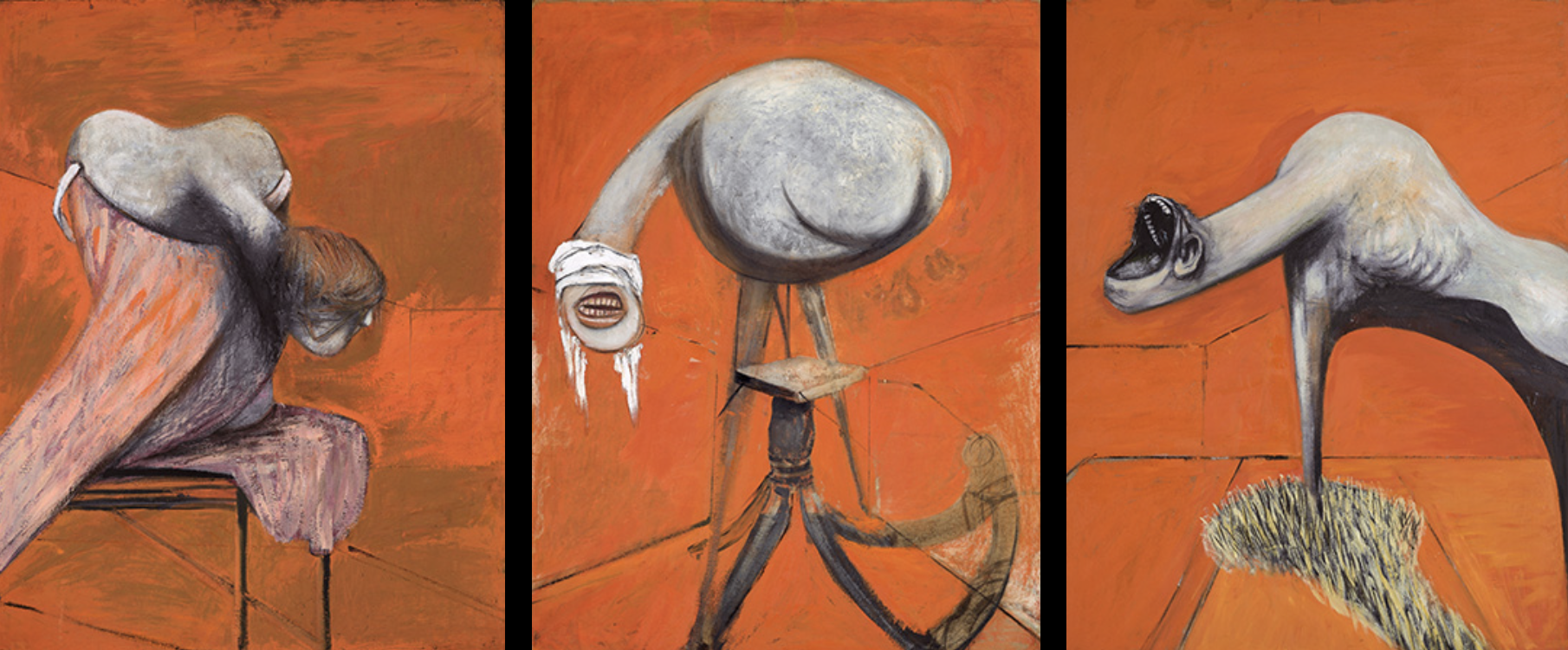

TRIPTYCH: IN MEMORY OF GEORGE DYER, 1971

Words by SAMO

Images from

The Estate of Francis Bacon

On the 26th of October 1971, painter Francis Bacon was opening his legendary retrospective at the Grand Palais, Paris; his status as a revered artist well and truly cemented. For a living artist to be awarded such an honour was rare, the last before him being Picasso in 1966, who himself was a huge inspiration on Bacon.

While Bacon’s career from an outsiders perspective was at its peak, his internal world was in chaos. Two days before the exhibition, staff at the Hôtel des Saints Pères found Francis Bacon’s lover, George Dyer, dead, slumped on a toilet set, an apparent suicide. Rather than let this scandal affect the opening of what was soon to be his greatest accomplishment, Bacon’s friends conspired with the hotel’s management to keep the death a secret for days. A conspiracy so effective that until 2016, biographers of Bacon maintained that the artist had no knowledge of the death until after the opening’s close.

It was this brush with death and violence that defined both Bacon’s personal and creative life. His fascination with the pain of existence and the horror of memory that become fuel for his creative career, giving him material that would sustain him for decades.

“All of our actions take their hue from the complexion of the heart, as landscapes their variety from light.”

THREE STUDIES FOR A CRUCIFIXION, 1962

From the early days of Bacon’s artistic career, critics were repulsed by his imagery, disfigured teeth, mutated limbs and soulless backdrops. Yet while other artists around him were exploring social movements and revolution, Francis Bacon was taking a more introspective approach. Diving into the depths of his unconscious to find an outlet for his darker desires.

Bacon: an avid gambler, drinker and masochist, lived on the fringes of society. His friends ranging from drug-addicts, east-London Gangsters and art scholars. It was his close relationships and fascination with the human body and its form that sculpted the vision for his art.

THREE STUDIES FOR FIGURES AT THE BASE OF A CRUCIFIXION, 1944

He preferred not to paint from life like his hero Picasso or contemporary painters, such as Lucian Freud, but rather he used the photographs of his friend John Deakin, crumbled up and torn, splattered with excess paint. It was this collaboration with Deakin that resulted in one of his most famous nude portraits of Henrietta Moraes in 1966. A twisted and contorted mass of flesh reminiscent itself of Picasso’s masterpiece Demoiselles d’Avignon.

HENRIETTA MORAES, 1966

HENRIETTA MORAES, 1950s

LEAF FROM BOOK, EADWEARD MUYBRIDGE, THE HUMAN FIGURE IN MOTION (DOVER PUBLICATIONS: NEW YORK, 1955)

As a self-taught artist, Bacon’s techniques were unconventional and perhaps, this is what separated him from the crowd. He used rags to smear paint across the unprimed back of a canvas, drew inspiration from books on oral diseases and copied haunting silhouettes from Eadweard Muybridge’s studies of bodies in motion.

While he did indeed take inspiration from cinema stills and distant almost impersonal works like that of Muybridge, it was his personal relationships that defined his more famous paintings. No relationship sums this up more than that that of the one he had with George Dyer.

In the wake of Dyer’s suicide, Bacon returned to the hotel in which the body was found. What he thought about and reflected upon during this visit will remain forever unknown, however whatever he did find was channeled into some of the most astonishing works of his career. Triptych May-June 1973 is a series of three images, inspired in form by early Christian art. Triptychs were traditionally three carved panels hinged together, depicting a religious scene. However, Bacon subverted this notion, using it instead as a form of catharsis highlighting the scene of the death of one of his greatest loves. The images of his lover, hunched over a toilet, dying of an overdose are both shocking and raw; brutal in their depiction of a relationship lost forever, reduced to a mere memory.

TRIPTYCH, MAY-JUNE 1973

TRIPTYCH, MAY-JUNE 1973

“My painting is not violent; it’s life that is violent.”

Francis Bacon was one of the masters of 20th-century art, a champion of art revered by the critics and a notorious partygoer and drinker. Yet when you delve into the context and background of his paintings, a much more sympathetic and delicate figure emerges. His life, much like his paintings was one of extremes, filled with luscious colours contrasting the depths of his darkest tragedies. A beautiful and tragic existence, but one that raises the age-old question “is there ever truly light without the darkness?“